Quality governance processes are essential for agencies to operate effectively. The evaluation of “good” governance is important not only for an agency but also for a state civil service. This is the clue for donors and reformers to base on when assessing the impact of policies and determining future development projects. Moreover, “good” governance evaluations are the factor determining the investment climate of a sector or country. A research paper of United Nation found that aid flows have greater impacts on development in countries with “good” governance. This writing aims to give a brief of theoretical knowledge on governance in public sector and provide a practical case-study in Australian civil service, where governance has been improved and responsive and accountable to both the Government and the public.

1.Definitions

1.1. Governance

What is governance? There is more than an answer to the most interesting but diversified phenomenon in public sector. Some says the way a society sets and manages the rules that guide policy-making and policy implementation[1] is often considered as governance. Others emphasis the concept of governance in public sector and discuss that the concept governance covers “the set of responsibilities and practices, policies and procedures, exercised by an agency’s executive, to provide strategic direction, ensure objectives are achieved, manage risks and use resources responsibly and with accountability.’[2]

Governance is a phenomenon that can be evaluated. It can be evaluated at three levels that are global level, national level and local level. On a global level, this concept can be compared across countries and over time, thanks to standardized data that can be applied to diverse cultures, economies, and political systems. On a national level, governance can be analyzed more comprehensively with more flexible and specific features. On a local level, governance assessment is mostly targeted in a geographical region[3].

1.2. Good governance

Governance is “good” when through it State can perform efficient allocation and management of resources to respond to collective problems. That means when a government has sufficient capacity to provide public goods of necessary quality to its citizens. The efficiency in this context is understood that states should be assessed on both the quality and the quantity of public goods provided to citizens[4]. And the policies that supply public goods are guided by principles such as “human rights, democratization and democracy, transparency, participation and decentralized power sharing, sound public administration, accountability, rule of law, effectiveness, equity, and strategic vision”[5].

As said by The Australian National Audit Office quoted in the Governance Framework 2013-2017 of Queensland government, the concept of good governance includes good governance in both performance and conformance. While good governance in performance is how an agency uses governance arrangements to contribute to its overall performance and the delivery of goods, services or programmes, good governance in conformance is how an agency uses governance arrangements to ensure it meets the requirements of “the law, regulations, published standards and community expectations of probity, accountability and openness”[6]. In a more general meaning, on a daily basis, governance is typically about the way public servants take decisions and implement policies.

2. Governance LEATIS principles

The governance framework is based on LEATIS principles of public sector governance. They are Leadership, Efficiency, Accountability, Transparency, Integrity, and Stewardship. Agencies need to have an approach to governance that enables them to deliver their outcomes effectively and achieve high levels of performance, in a manner consistent with applicable legal and policy obligations.

3. The case-study of Department of Human Services of Australia

This case-study is a good example of how changes in governance brought together a range of disparate service delivery agencies into a holistic service delivery system which is responsive and accountable to both the Government and the public.

3.1. Brief introduction

The Department of Human Services (DHS) is responsible for the development of service delivery policy and provides access to social, health and other payments and services. It was created on 26 October 2004 as part of the Finance and Administration portfolio. The Human Services Legislation Amendment Act 2011 integrated the services of Medicare Australia, Centrelink and CRS Australia on 1 July 2011 into the Department of Human Services.[7].

3.2. Challenges

Implementing the new arrangements was a big obstacle to tackle. Each of the service delivery agencies in the civil service had developed their own operating systems, culture and objectives. Therefore, the comprehensive picture was non-systematic. Consequently, big change driving force was essential to not only the administrative procedures but also the culture required an overhaul as well. Additionally, some agencies, such as those that had operated under the governance of boards, did not have experience in delivering whole of government objectives and had not been required to be responsive directly to a Minister in their day-to-day operations. Some agencies were also looking to make improvements, for example to provide more consistent services with shorter waiting times.

3.3. System description

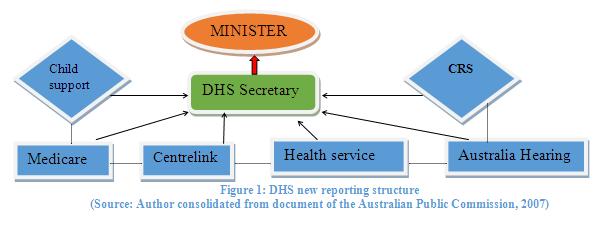

The Human Services portfolio was created partly in the review of corporate governance of statutory authorities and office holders. The heads of four of the service delivery agencies (Medicare Australia, Centrelink, Health Services Australia and Australian Hearing) now report directly to the Minister through the Secretary of DHS. The other two service delivery agencies, Child Support Agency and CRS Australia, are legally part of DHS and therefore report to the Secretary. Prior to the creation of the department, two of the larger agencies (Centrelink and the former Health Insurance Commission, now Medicare Australia) were accountable to boards. The portfolio’s governance structure and operating systems are based on strong leadership on the basis of government objectives and frequent monitoring of performance against these objectives.

3.4. Improving governance status

Changes needed to be driven strongly across the portfolio, with leadership and an overarching framework provided by the portfolio department. Firstly, more regular meetings were held between authority levels, who are the Minister, the Secretary and agency heads, and implementers. The working contents focus on monitoring previously agreed key performance indicators, discussing the strategic directions of the portfolio and identifying any potential problems and what will be done to address them. Similarly, agency heads meet bi-monthly or more frequently to discuss and resolve matters relating to all agencies in the Human Services portfolio. Secondly, an ‘escalation system’ was established to help identify potential high-risk problems early and escalate them to higher levels of management for resolution before they get out of hand. For example, this escalation system has been applied to Centrelink’s computer system which can potentially impact on hundreds of thousands of citizens. The third change to mention was that the department also focused on improving client service across the portfolio. A range of initiatives was implemented including expansion and enhancement of services, improved technology, simpler forms, and effective client service collaboration between agencies. An example of this is the Myaccount project, which uses technology to save time and effort for customers and which involved considerable work across Human Services agencies under the governance of the core department. This is a program that allows members of the public to sign-on to their Child Support Agency, Centrelink and Medicare accounts with a single username and password, providing greatly improved client service[8].24

3.5. Monitoring

The governance model applied by DHS includes frequent and high-level lines of reporting, accountability and transparency, ensures that problems are identified and addressed early. The department receives monthly reports from each of its agencies, outlining operational and financial performance against pre-determined goals and objectives. All budget measures that are undertaken by the portfolio agencies are monitored by the department. The monthly reports are thoroughly analysed in preparation for a governance meeting held between the Secretary and each of the portfolio agency heads. Service delivery is reviewed and discussed at these governance meetings. In fact, the financial performance and position of the Human Services agencies are regularly analysed, providing important input to the governance meetings[9].

3.6. Benefits

The most valuable and obvious benefits of this renovation showed on the establishment of the new department and the co-ordinated arrangements for the new Human Services portfolio, which have ensured greater responsiveness to the Government and better integrated, consistent and more timely services for citizens. Additionally, it is demonstrated over time that the department has achieved economies of scale as well as clearer accountabilities by identifying and implementing more effective and efficient approaches across the portfolio as a whole as well as in all its separate parts.

4. Key findings

From the summary of theoretical knowledge on public sector governance and through governance improvements shown in a case of DHS in Australian civil service, we can draw out some key findings of the writing as follows:

1. The crucial things to improve governance in public sector are strong and clear leadership, which can help successfully bring together disparate services, and establishing good working relationships with portfolio agency heads.

2. For the case of a comprehensive change, which may embed widespread cultural change, including consolidation of very different entities, it is a must to clearly defined the change needs and it also need a strictly decisively management to make expectations to be absolutely clear.

3. Last but not least, it requires to have documented and well-understood approaches and protocols to quickly and precisely escalate notification of high-risk problems or potential problems. It will be more feasible than waiting for a problem to arise before determining the processes that need to occur ./.

Nguyen Quynh Giang M.Sc.

Institute for State Organizational Sciences

[1]Director of Division for Public Administration and Development Management, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, January 2007, New York.

[2] ANAO and Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2006, Implementation of Programme and Policy Initiatives: Making Implementation Matter, Better Practice Guide, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, p.13 <http://www.anao.gov.au/uploads/ documents/Implementation_of_Programme_and_Policy_Initiatives.pdf>

[3] United Nation, Literature review on governance, 2007, New York

[4] Rotberg R.I., “Strengthening governance: ranking countries would help”, The Washington Quarterly (2004-05)

[8] Australian Government, Australian public commission, Good governance, 2007